A Service of Nine Lessons

and Christmas Carols

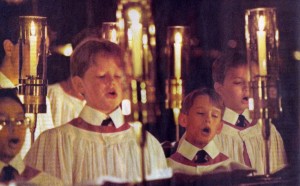

The

format of the Service of Nine Lessons and Christmas

Carols sung every year in All Saints church follows

closely the format of the service first offered in King’s

College,

The

broadcast of the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols

from the chapel of King’s College Cambridge seems

almost as ingrained in our traditions of Christmas as

Santa Claus and the turkey. So it’s no surprise to

discover that the service is actually a relatively recent

phenomenon – it only dates back to 1918 with radio

transmission starting in 1928.

Nor has

it been an unchanging ritual, as a fascinating CD

released in November 2005 reminds us. On Christmas Day:

New Carols from King’s contains 22 of the carols

commissioned for the service by Stephen Cleobury since he

arrived in 1982 as director of music.

This year’s

new carol will be a setting of Away in a Manger by

John Taverner; something by John Adams is lined up for

the future. With compositions by King’s graduates

Thomas Adès and Judith Weir, as well as major names such

as Harrison Birtwistle and Arvo Pärt, already in the

bag, King’s can fairly claim to be bucking the

wretched decline in the quality of church music.

The

commissions are very much to the credit of Cleobury, only

the fourth director of music at King’s since 1929.

He isn’t a radical, he claims, and he arrived with

the modest intention of preserving “the virtues if

choral discipline”. But inevitably over the decades

he has moulded a change in style, and the choir no longer

sounds as it did under the regime of his predecessors.

“I

suppose I’ve developed a more open, natural and less

pure sound” Cleobury explains. The almost genteel

refinement that one notices in recordings of the choir

under Boris Ord (in charge from 1929-1957) has come

closer the to the freer, more abrasive tone cultivated in

the ‘50s and ‘60s by George Malcolm at

Westminster Cathedral and George Guest at St. John’s

Cambridge, in imitation of the European boys’ choirs

of Montserrat and Vienna.

More

change is on the way, thinks Cleobury, as the musical

education of the singers who enter the choir changes.

“They listen to a far wider range of music than my

generation did, and it’s marvellous that ‘classical’

is no longer isolated in its own little box. But the

standard of sight reading has gone down, and it troubles

me that you can now do A-level music without studying

harmony and counterpoint.”

Cleobury

also points out that “the number of candidates has

gone down by about half over the last years - we now have

about twenty applicants for four or five places. I put

this down to broader trends – less church-going, the

disappearance of music from so many primary schools.

Fortunately, the standard of the people we see remains

very high, and because of the reputation of King’s,

we’re not struggling or compromising in the way that

some other boys’ choirs are.” There is no

question of admitting girls at present.

The King’s,

choir has probably produced as many first-rate classical

musicians over the last 30 years as any of our

conservatoires (Gerald Finley, Mark Padmore and Andrew

Kennedy among them) but Cleobury is adamant that “we’re

not just a professional training-ground. It’s

equally important that we feed into our great tradition

of amateur music-making.”

He doesn’t

want the choir to measured by its commercial success

either – “it’s what we do day-to-day in

the chapel that really counts” – but it is

clearly gratifying that King’s remains “brand

leader” and has just signed a new five-year contract

with EMI Classics. It continues to tour out of term-time,

and has recently performed across the U.S. Europe and the

For the

senior choral scholars, the travel makes their parallel

lives as university undergraduates extremely taxing, but

they seem a happy team, conscious of being an elite and

grateful for the opportunities; about half of them will

make classical music their career.

The

junior choristers all boarding pupils at the prep school

attached to King’s, take it in their stride,

expressing certain impatience with Renaissance music (“too

repetitive”) and preferring the grander emotional

range of Elgar, Parry and Walton, though “people

like Bach are good too”.

As well

as the daily routine of choir practice, they all have

individual singing lessons designed to groom them in the

rudiments of god technique - deep breathing supporting

diaphragm, keeping your tongue forward and your mouth

open in a “hot potatoes” position. They also

have to adjust to the chapel’s acoustics – the

echo resonates for between four and seven seconds,

according to frequency ranges.

Although

the choir has been much recorded in since the 1960s,

evidence of its earlier work is sadly scarce, not least

because the BBC has lost or destroyed most its broadcast.

So the emergence of a cache of tapes from 1956-1959,

recently donated to the British: Library Sound Archive,

is of great historical importance.

These

were made secretly on a Grundig reel-to-reel machine by a

King’s undergraduate, Roger Martin, in conspiracy

with the choral scholar Brian Head, and although the

sound is very crude, they chart the choir’s

transformation fro the strict and even prissy elegance

nurtured by Boris Ord to the more expansive approach of

David Willcocks (1957-1973).

One track

and in particular stands out: the boy soprano Richard

White singing Ihr haht nun Traurigkeit, from

Brahms’s German Requiem, in 1956. It

encapsulates in one achingly sweet and seraphically pure

treble the unique magic of King’s.

Rupert

Christiansen.

Daily

Telegraph

Reproduced

by kind permission of the Daily Telegraph.